A Tale of Two Cities: Johannesburg and Cape Town

South Africa, a country of unreal beauty, teeters on the brink of profound change. I stood on a rocky beach watching penguins shuffle along the sand. A few miles across the water, Table Mountain rose behind the sprawling, gleaming city of Cape Town. It was a breathtaking scene—one that Nelson Mandela may have glimpsed from Robben Island, though for 18 years he spent it in a 6’ by 6’ prison cell with no outside windows.

A week earlier, we had landed in Johannesburg, a city of tension and contradiction. From the sleek international airport, we boarded a modern train that whisked us to our 5-star American branded hotel in Sandton, an affluent suburb of glass and steel skyscrapers and luxury malls. Yet the streets were eerily empty.

View from our hotel room in Sandton, Johannesburg, SA

“Do not walk outside,” warned the armed security guard at the hotel entrance.

“Sir, do not go anywhere alone,” echoed the receptionist kindly as she handed us our room keys.

It became clear within the first hour—this was not a city meant for walking. We rented a car and hired a young chauffeur in a well-cut suit and tie who would drive us for the next three days. From a distance, Johannesburg resembled any large American city—clusters of high-rises, sprawling suburbs and intersecting freeways. But up close, the cracks showed. Entire neighborhoods remain divided—townships of crumbling shacks and neglected infrastructure for the poor, high-walled enclaves with barbed wire and private security for the rich.

“The security business is very good,” said a handsome young man we met later on safari, vacationing with his wife. “But we’re looking to get out.”

“Where would you go?” I asked.

“USA would be great, but it’s hard to get in. My sister is in Atlanta, but we’re thinking of England or Holland.”

“We have no future here,” his wife added with a resigned shrug.

The country has a huge electricity shortage and 6-8 hour power cuts are the daily norm. All the hotels, businesses and houses in the upscale neighborhoods have generators and we would know when they kicked in by the brief flickering of lights and a low humming sound. At night from the rooftop bar of our hotel we looked over the city and could easily spot the brightly lit areas where the rich and privileged lived and the dark areas where the poor lived in misery.

The country is going through a major economic crisis. It is Africa’s largest economy and a permanent member of the G20 and the per capita income on a PPP basis is an impressive $15,500, but the disparity in income is astounding. Unemployment hovers at around 35% and only 41% of working age adults have any kind of job. Over 1.5 million of the more skilled workforce has emigrated since the end of Apartheid in 1994.

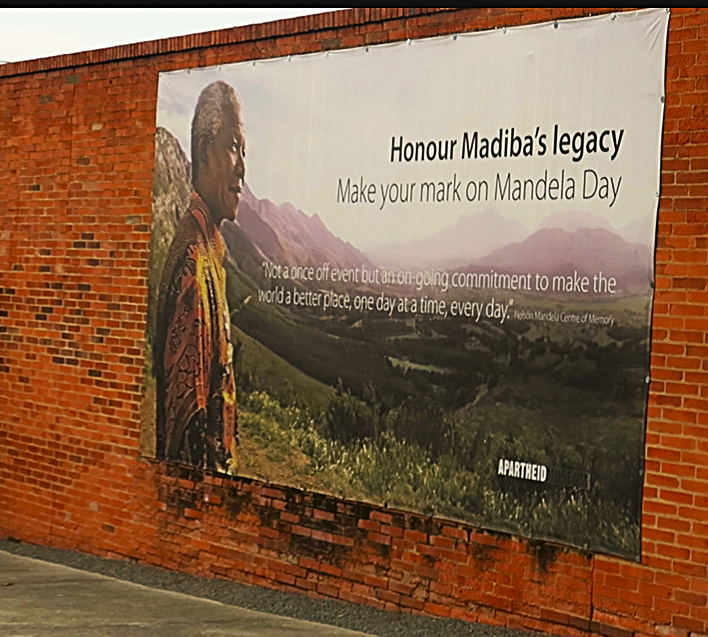

One morning, we visited the Apartheid Museum—a stark, unforgettable experience. The architecture resembles a prison: cold, geometric, intimidating. Visitors are randomly assigned a “White” or “Non-White” ticket at the entrance. I walked through the “Non-White” entrance, immediately surrounded by harsh metal bars, narrow corridors, and hostile signage. It was like stepping into history’s shadow—an immersive portrait of institutionalized oppression. Another section called “Journeys” featured life-sized images of early migrants, drawn to the city during the Gold Rush, displayed on translucent glass. Walking among them gave the sense of stepping into their stories. The museum’s Mandela exhibit was especially powerful, tracing his journey from activist to prisoner to president.

Outside the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, SA

Later, we visited Soweto, abbreviation for South Western Township—South Africa’s most famous township, a name synonymous with resistance. Spread over 77 square miles and home to more than 1.2 million people, it is a living monument to struggle and resilience. Originally built in the 1930s with tiny “model homes” of just 400 square feet, Soweto has grown into a sprawling community where informal housing leans precariously against old foundations.

Mandela’s home in Soweto – now a museum

Vilakazi Street was buzzing with tourists and school groups. It’s the only street in the world to have been home to two Nobel Peace Prize winners—Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Mandela’s former home is now a museum, still bearing bullet holes from police raids. The area, though now bustling with cafes and gift shops, holds a heavy sense of history.

There is no memorial to the hundreds of schoolchildren killed in the deadly Soweto Uprising of the 70’s, but in another irony, the FIFA World Cup Finals in 2010 were held in a stadium on the outskirts of this area.

Not far from there stand the Orlando Towers, each over 33 storey tall and dwarfing everything around—once part of a coal power station, now painted in bright murals. One tower advertises local businesses, while the other offers bungee jumping and rock climbing for the adventurous tourist. This strange juxtaposition of squalor and tourism felt odd—South Africa rebranding its past while still wrestling with its future.

The Orlando Towers, Soweto, Johannesburg, SA

We then left the city behind for Pilanesberg National Park, 120 miles and a 3-hour drive away. The road trip was scenic—rolling hills, lakes, and small picturesque towns peeking from behind concrete walls, while poverty stricken, rundown but colorful villages were filled with people and children playing. On safari, we spotted elephants, zebras, giraffes, rhinos, and hippos lazing in a lake. It was an oasis of calm after Johannesburg’s intensity.

Cape Town greeted us with natural grandeur—Table Mountain towering over a basin-shaped city that rolled gently to the sea. We drove past townships spilling over their walls, makeshift homes of corrugated metal and tarp. Yet minutes later, we entered neighborhoods of massive mansions perched above the waves. Cape Town’s contrasts were just as stark.

Driving in to Cape Town, SA

“You can walk around,” said the receptionist at our hotel near Table Mountain. “But take a taxi after dark.”

“Do you live nearby?” I asked.

“No, Sir. I live in the township.”

That answer echoed again and again. Most of the working class lived far away, commuting for hours by bus. Even the rental car agency was owned by two Europeans—the man running the office smiled when I asked if it was his own business.

“No, Sir. I just work here.”

An Uber driver laughed when I asked why he didn’t buy his own car. “What, Sir? Me buy a car! No way! No one gives us a loan. No one.”

View of the city from the V&A Waterfront, Cape Town, SA

The colorful Bo-Kaap neighborhood, Cape Town, SA

We took the Swiss built glass-walled cable car up Table Mountain—an unforgettable five-minute ascent, the car slowly rotating as the city receded below. From the summit, we could see the peaks and coastlines stretching for miles. In the distance, Robben Island sat like a shadow in the Atlantic.

View of the city from the cable car up to Table Mountain, Cape Town, SA

At the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront, we boarded a ferry to the island. Our guide was a former inmate—soft-spoken and dignified—who had served time in the 1980s alongside Mandela. He walked us through stark dormitories and Mandela’s preserved cell. Robben Island had no modern security—escape was impossible with the cold Atlantic serving as a natural barrier. As we explored the island, we spotted a colony of penguins waddling by. I wondered whether Mandela had ever seen one during those long years.

Mandela’s cell where he was imprisoned for 18 years, Robben Island, SA

Penguin colony, Robben Island, SA

View of Cape Town from Robben Island, SA

Driving along the Cape Peninsula to the Cape of Good Hope felt like California’s Highway 1—cliffside roads, pristine beaches and turquoise water. We stopped at Boulders Beach to admire another penguin colony. Later, as we drove through the national park, traffic halted—two ostriches stood in the middle of the road. One bent its neck to my window, made eye contact, and slowly walked away—an image I’ll never forget.

On the drive to the Cape of Good Hope, SA

We finished our trip with a visit to the Winelands. Stellenbosch charmed us with its art galleries and whitewashed colonial buildings. Spier Wine Farm, over 300 years old, offered lakes, sculpture gardens, and tastings of elegant Chenin Blancs. The drive to Franschhoek was one of the most scenic I’ve ever taken—rolling vineyards under towering mountains. At Haute Cabrière, a winery built into a hillside, we enjoyed a full tasting in their cool stone cellar.

The town of Stellenbosch, SA

Wine tasting at a winery, Stellenbosch, SA

On the drive to Franschhoek, SA

Wine tasting at Haute Cabriere Winery, Franschhoek, SA

The next morning, we flew to Kruger National Park. As the plane lifted off, Cape Town shrank below us, but the memories lingered—of beauty and imbalance, of history and hope. South Africa is a country of fierce contrasts: raw and elegant, broken and brilliant. And it has stayed with me ever since.

Leave a Reply to Jerrold Satterfield Cancel reply